Mount Wellington, home of the isopod studied in Tasmania

Isopods are common marine, freshwater, and terrestrial animals with seven pairs of legs. The one most familiar to you is probably the one that rolls up in a ball when disturbed after you pick up your flower pot. Most are flattened so top and bottom appear close together. But the one in Tasmania is part of an extremely old group and does not have that flattening, in fact it appears as though it is flattened with the sides closer together.

Mount Wellington is a little over 4,000 feet tall. The summit is only a few miles from downtown Hobart, as shown from the harbor on the Derwent River below. Darwin had difficulty reaching the summit, which he did late in the day on his second try. It was much easier for me because a road had been built to very close to the summit. The back side of the mountain still has tree ferns as noted by Darwin in his Voyage of the Beagle along the Northwest Bay River which is fed by the mountain top pools.

The isopods on Mount Wellington and others in the same suborder are now restricted to the Southern Hemisphere. Although first discovered in well water in New Zealand, most species are found in Tasmania, with only three in South Africa. Their discovery came after Darwin's visit to Tasmania and Mount Wellington where he may have trod through the pools where they are found as he gazed out from the summit and saw the views below.

What looks like moss covered rock is really the dense growth of branches of a composite noted below.

The pools around the round green composite Abrotenella fosteroides in the first picture closeup were sampled periodically for a year.

This view from just beyond the pool containing the isopods shows Ralph's Bay and the Tasman Peninsula to the East of the summit lookout.

At least a three year life cycle from egg to isopod to egg

All the isopods in one kitchen strainer scoop were collected, counted, and measured. During the Australian summer they were inactive in the dried but damp pools. When pools refilled in the spring, a new batch of young were released from the brood pouch (formed from plates extending from basal segments of four pair of legs) for the annual crop of young. A maximum of 19 young or eggs were counted in pouches from other samples.

If you notice carefully you can see two or three age classes in the November sample. In the May sample only two of the young from the previous date were included as the new young became quite numerous. A possible middle group from November is merging with the adults. Relatively few adults were found in the July sample, although in August they were abundant. Part of the disparity of adult numbers was probably due to the fact that many females with eggs were abundant under the green composite shown, while my samples came from the flocculent sediment in the deeper part of the pool.

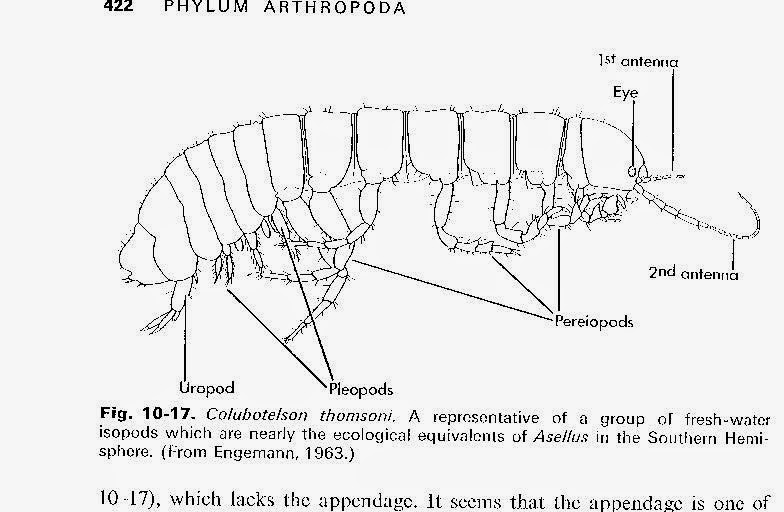

The pools were above the timber line on the mountain and had snow and ice part of the winter. But it did not appear a factor in reducing the number of generations to one per year because a population of closely related isopods had the same growth pattern at sea-level on nearby Bruny Island. Just for the record for interested zoologists, the isopod is Colubotelson thomsoni in the suborder Phreatoicoidea. It is usually viewed from the side because the flattening make a specimen lay in that position as in the photo above and the figure below.

The pleopods beat in a channel made by downward projections of the sides of the abdominal plate. They are the respiratory organs of the isopod, although in the male a portion of the second one is modified for sperm transfer. This region of the abdomen retains the segmented nature whereas in the Michigan isopod (Asellus) the segments of the exoskeleton are fused. Because of the flattening, its pleopods are exposed and the third one has a protective plate shielding the ones behind it. The first two, unprotected are greatly reduced but the sperm transfer appendage of the male is still functional. So both sexes have the respiratory function of the first two pleopods lost by selection driven by the selective value of the arrangement for the male.

The eggs of the Tasmanian isopod have about twice the diameter of the Michigan ones. The egg shell is also about twice as thick. Development to hatching takes several months in contrast to about two weeks for the Michigan one. In a upcoming post I expect to show the egg appendage of the Michigan one which may help in its speedy development.

Joseph G. Engemann June 1, 2014

No comments:

Post a Comment